BACK TO TOP

LEDs and digital rain: Neil Patel on creating the world of ‘Civilization to Nation’

The New York-based set designer of Dickinson/Pretty Little Liars fame takes us through his process and detailing for Feroz Abbas Khan’s grand spectacleBy Avantika Shankar | 18th Apr 2023

For set designer Neil Patel, every story is a research project. Best known to Indian audiences for his work on Feroz Abbas Khan’s ‘Mughal-e-Azam: The Musical’, the Obie Award-winning designer works extensively across theatre, film, opera and television, and has visualised worlds as glossy as in Zoya Akhtar’s Dil Dhadakne Do, as gritty as Jo Bonney’s Broadway production of ‘Father Comes Home’ from the Wars, and as opulent as Amon Miyamoto’s operatic production ‘The Marriage of Figaro’. A part of Patel’s dedication to real-life detail stems from his early training in architecture, which he pursued at Yale, although his love for creative collaboration and experimental ideation eventually drew him to the performing arts. He later went on to study set design at the University of California in San Diego and scenography at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan, worked briefly at a theatre in California, and eventually began pursuing his craft professionally in New York. Even after an accolade-sprinkled career and two Obies for sustained excellence in theatre, Patel acknowledges that every new project is entirely unique in terms of the demands it makes of him. “You’re always tasked with learning about something you never thought you would be learning that much about,” he says.

This is especially true of his work for Feroz Abbas Khan’s ‘The Great Indian Musical: Civilization to Nation’, which showcases the spectrum of performing arts across the history of the South Asian subcontinent, leading up to the creation of the modern Indian state. “I need to know the accurate historical information, and it needs to be based on authenticity,” he expresses, adding “I am not doing a museum piece. It needs to have its own aesthetic in a way that is exciting for the viewer.”

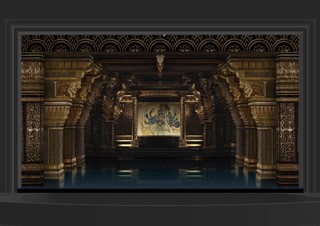

Patel has combined digital projection with dimensional scenery. The black voids in this image are high-definition LED screens that accentuate the temple columns

Patel has combined digital projection with dimensional scenery. The black voids in this image are high-definition LED screens that accentuate the temple columnsPatel was especially excited by the fact that ‘Civilization to Nation’ would be the opening show for the NMACC’S Grand Theatre and would therefore be showing off all its state-of-the-art technology. “This was a very exciting opportunity to not only tell this story but also show off the capabilities of this space,” he expresses. Patel worked closely with projection designer John Narun, who was also a collaborator on ‘Mughal-e-Azam'. “We have combined modern techniques, like projection in the form of digital imagery, with dimensional scenery.” The black voids in this particular image are high-definition LED screens that extend and accentuate the scenery—in this case, the temple columns. “We're used to enormous amounts of visual stimulus on our phones and our computers, so we're also creating theatre now for people who are used to that level of visual stimulus refinement of imagery,” he adds. “Technology allows us to keep up with it on stage.”

Patel created the physical elements first. Only two of the arches in this image are real–the rest is an extension created through LED imagery

Patel created the physical elements first. Only two of the arches in this image are real–the rest is an extension created through LED imageryPatel was especially excited by the fact that ‘Civilization to Nation’ would be the opening show for the NMACC’S Grand Theatre and would therefore be showing off all its state-of-the-art technology. “This was a very exciting opportunity to not only tell this story but also show off the capabilities of this space,” he expresses. Patel worked closely with projection designer John Narun, who was also a collaborator on ‘Mughal-e-Azam'. “We have combined modern techniques, like projection in the form of digital imagery, with dimensional scenery.” The black voids in this particular image are high-definition LED screens that extend and accentuate the scenery—in this case, the temple columns. “We're used to enormous amounts of visual stimulus on our phones and our computers, so we're also creating theatre now for people who are used to that level of visual stimulus refinement of imagery,” he adds. “Technology allows us to keep up with it on stage.”

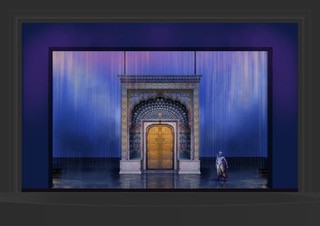

LED imagery has got to a point where effects such as life-like simulations of rain and smoke are relatively easy for theatre-makers to create

LED imagery has got to a point where effects such as life-like simulations of rain and smoke are relatively easy for theatre-makers to createOne of the biggest boons of digital imagery is that set designers can simulate weather in a way that feels realistic to the audience but requires zero additional resources on stage. Scenes such as this one, which depict rain, would have been created with real water, leaving behind a wet stage and a huge liability for clean-up. Now, LED imagery has got to a point where effects such as this are both effective, theatrically speaking, and relatively easy for theatre-makers to create. What’s more, traditional stagecraft often requires large set pieces to be “rolled” or “flown” in through elaborate rigs, which takes time. “With LED imagery, we can completely change the stage and the mood almost instantly,” expresses Patel. This, when employed in tandem with nuanced lighting design, lends a cinematic quality to theatre that is especially stunning to witness.

The skill of a set designer lies in knowing when to create spectacle on stage, and when to leave room for other collaborators. “We don't want to overwhelm the performers, which you can do very easily,” he says, “We need to make sure that the spectacle that we're creating is supporting the performance of the story.” Although the vision of the play was driven by director Feroz Abbas Khan, ‘Civilization to Nation’ is a culmination of the creative input of multiple choreographers, each of whom had a hand to play in how their respective sets would eventually be designed. “John Narun, Donald Holder and I met with the choreographers, and they brought their own imagery and inspirations to the process,” Patel explains. “Obviously, there were physical requirements for floor space and props, and physical set elements they would need for the choreography, so we worked closely with them to make sure that was integrated into the design.”

Patel is careful not to overwhelm the performers with spectacle and opts for a minimal touch when required

Patel is careful not to overwhelm the performers with spectacle and opts for a minimal touch when required“In ‘Civilization to Nation’, we're telling the story of this vast and complex civilization, culminating into the idea of a nation,” he explains. “What’s powerful is we’re creating a visual language that is exciting, and perhaps something people haven’t seen before.” The Ganesha statue is cast in fibreglass from a hand-carved clay model made by local artisans. The larger-than-life, but immensely intricate, set piece, is a testament to the detail Patel has put into his design. “In theatre or opera–or any live performance–nobody can control what the audience will choose to focus on, so you're much more aware of creating a space that is seen from multiple viewpoints,” says Patels. “You have to design for what the human eye can see at a distance of twenty or forty metres, so you have to think very carefully about the level of detail you’re putting in.”

The Ganesha statue that features in the production is cast in fibreglass from a hand-carved clay model made by local artisans

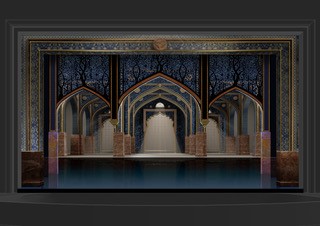

The Ganesha statue that features in the production is cast in fibreglass from a hand-carved clay model made by local artisansStill, Patel cautions sticklers for historical accuracy that we often tend to forget that a lot of the structures we’re used to seeing as bare-bones ruins might actually have been painted in bright colours during their heyday. “Our perception of them now is as these ancient ruins,” he says, “I am trying to put life back into them, so to speak. To illustrate his point, he references his design for the arches and jaalis in this particular set piece. “They’re taken from actual references,” he admits, “But some of these elements would be made of stone, or some of them would be proportioned slightly differently. To most people, it still feels authentically like Mughal architecture, but it has been theatricalised through the use of colour, or proportioned slightly differently than it would be in reality.”

Patel relied on references from authentic Mughal architecture for the arches and jaalis in this set piece but added imaginative twists to make them appear spectacular

Patel relied on references from authentic Mughal architecture for the arches and jaalis in this set piece but added imaginative twists to make them appear spectacular“One of the difficult things in designing this was making a cohesive theatrical presentation of elements that are actually very different,” expresses Patel. “We’re trying to put them together in a way that they feel connected, like they’re rendered with the same sensibility.” Patel describes the effect as “being drawn by the same hand,” so that the play seemingly exists in a single, unified world. “This play takes place over millennia, and showcases very different architectural styles and cultural influences,” he adds, “So we have to make them all true to themselves but unite them in the way that they're rendered.” This particular set comprises a fully dimensional doorway that the dancers can interact with, while the imagery of the palace has been rendered through digital imagery. “Hopefully, the piece exists in a way that is cohesive to the average viewer, and they won't necessarily be able to tell what is digital imagery and what is real, Patel adds, “It all lives together harmoniously.”

Feroz Abbas Khan’s ‘The Great Indian Musical: Civilization to Nation’ will showcase at The Grand Theatre, Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre, in Mumbai from April 3 to 23, 2023.

This set comprises a dimensional doorway that the dancers can interact with, while the imagery of the palace has been rendered through digital imagery

This set comprises a dimensional doorway that the dancers can interact with, while the imagery of the palace has been rendered through digital imagery